How SQL injection prevention works, and why it’s still relevant

March, 2020 · 6 min read

Since the early days of the web, one of the most common vulnerabilities has been and still is SQL injection. It has led to countless stolen login credentials, credit card numbers, compromised websites, and denial of service attacks.

Fortunately, preventing SQL injection is straightforward, using parameterized queries. But what is it about parameterized queries that keep you safe? Similarly, using prepared statements is another way to prevent SQL injection. Are prepared statements and parameterized queries the same thing?

Two decades later, it’s remarkable how SQL injection is still relevant. Why is this the case? Is there something we can do about it?

How is data moved from an application to a database?

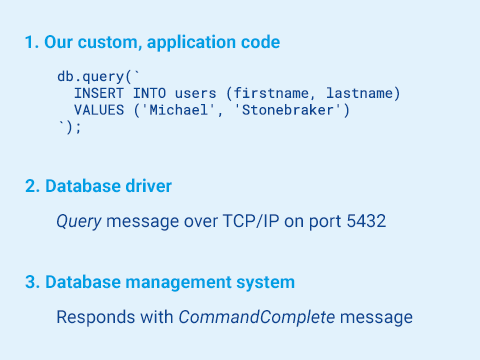

First, let’s remind ourselves how data gets inserted into and fetched from a database.

Typically, we’d use a driver (also called a client library or adapter) to interface with a database. We write an SQL statement and pass it to a query() or execute() method provided by that driver. The driver, in turn, communicates with the database using the protocol of whichever DBMS we’re using.

Parameterized queries and prepared statements

If we look at most database drivers’ query() or execute() methods, they also support a second argument. If we pass the values of our SQL statement to it and substitute the values of our original statement with placeholders, we are performing a parameterized query (also known as parameter binding).

const firstname = 'Michael';

const lastname = 'Stonebraker';

database.query(`

INSERT INTO users (firstname, lastname)

VALUES ($1, $2)

`, [firstname, lastname]);How a parameterized query keeps us safe from SQL injection varies from driver to driver, and partly depends on the DBMS.

Some DBMSs, such as PostgreSQL and MySQL, support something called prepared statements as part of their protocol. For PostgreSQL, instead of sending just a Query message, the query happens over three messages: Parse, containing our SQL statement with placeholders; Bind, containing our values from the second argument; Execute, instructing the DBMS to run the prepared statement. By design, prepared statements are safe from SQL injection.

Drivers of DBMSs that don’t support prepared statements protect against SQL injection through a different mechanism: the values passed to the second argument are first escaped, and then substituted back. The driver then sends a single query to the DBMS. As the driver has escaped all values, the intended SQL statement cannot be altered by them.

However, it’s not a guarantee that drivers of DBMSs that do support prepared statements use them. For instance, while node-postgres uses prepared statements for parameterized queries, psycopg2 merely performs escaping.

firstname = "Elliot"

lastname = "Alderson'); DROP TABLE users;--"

cursor.execute("""

INSERT INTO users (firstname, lastname)

VALUES (%s, %s)

""", (firstname, lastname))

# INSERT INTO users (firstname, lastname)

# VALUES ('Elliot', 'Alderson''); DROP TABLE users;--')So, to summarize: parameterized queries are something database drivers provide, while prepared statements are something DBMSs have as part of their protocol. Performing a parameterized query protects against SQL injection – whether it accomplishes that through escaping or prepared statements depends on the driver.

Are prepared statements better?

One could argue that prepared statements are more foolproof than escaping, even though they both prevent SQL injection. When escaping, the burden is on the driver to do it properly – something that’s hard to verify as users of that driver. However, this shouldn’t be a concern as long as we are using known and mature drivers.

On the flipside, prepared statements do have a minor cost in that they require more round trips to the database. For the vast majority of cases, it’s not something we need to factor in. If it is, it’s a sign we have other problems to solve first.

What about the rest of the SQL statement?

Neither parameterized queries nor prepared statements allow us to use placeholders for the rest of the SQL statement.

If we want dynamic SQL statements, a solution is to form the dynamic parts using a list of allowed values (e.g., ASC or DESC). Another solution is to have a list of entire statements. Our code then derives which item in the list to pick from user input.

Why is SQL injection still relevant?

There are great tools at our disposal, so why is SQL injection still a top threat? While we can discuss from a broader perspective – security is an afterthought, lack of formal training, functioning software does not equate secure software – let’s scope the discussion to the code level.

The main challenge, I believe, lies in the subtle difference between vulnerable and safe code. For someone who doesn’t understand SQL injection, seeing strings passed to the second argument vs. concatenated or interpolated in the first argument looks all too similar. And because there are cases where we do want to use variables inside the SQL statement, it’s not apparent for that same person what precautions we’ve taken.

cursor.execute("""

INSERT INTO users (firstname, lastname)

VALUES ('{}', '{}')

""".format(firstname, lastname))

cursor.execute("""

INSERT INTO users (firstname, lastname)

VALUES ('%s', '%s')

""" % (firstname, lastname))

cursor.execute("""

INSERT INTO users (firstname, lastname)

VALUES (%s, %s)

""", (firstname, lastname))

cursor.execute(

"INSERT INTO users (firstname, lastname) "

"VALUES ('" + firstname + "', '" + lastname + "')"

)

cursor.execute(f"""

INSERT INTO users (firstname, lastname)

VALUES ('{firstname}', '{lastname}')

""")Additionally, some SQL tutorials have no code snippets containing parameterized queries. If we don’t bother (or know to bother) looking further, we build on top of those snippets and introduce vulnerable code.

So, what can we do?

For starters, maintainers of SQL tutorials, particularly the ones ranking highly on Google, should consider changing their examples to parameterized queries – including examples where parameterizing the query is unnecessary.

In software, there’s this concept called secure by default. XSS, another top threat, was all the rage fifteen years ago, topping the OWASP list in 2007. Today, it’s not as prominent in part due to something web frameworks changed about themselves: variables inside of templates are output safely by default, one way or another. While there are situations where you want to turn off this behavior, there’s a higher likelihood you’ll study the consequences. React, for instance, is explicit in alerting you even at the API level.

const text = '<strong>Good morning!</strong>';

// treated as text

const safePost = <div>{text}</div>;

// treated as HTML

const unsafePost = <div dangerouslySetInnerHTML={__html: text} />;Could a similar change happen for database drivers? Perhaps it’s the responsibility of drivers to change their APIs, so the query method only supports parameterized queries. The non-parameterized version would require you to call another method. It would certainly alleviate the subtlety problem. Such a change would undoubtedly come at a cost: an uglier API and breaking backward compatibility.